Paradigm shift needed for the GCF?

14th April 2017 by CMIA

Just before the latest Board meeting of the GCF we posted a rather tongue-in-cheek link to the webcast [1]: “Better than Netflix! The next meeting of the GCF Board will be live-streamed.” Little did I know how accurate an observation this would turn out to be, for the meeting turned out to be – by the standards of such august bodies – quite a bunfight at times.

NDCI Global, 14 April 2017 by Ian Callaghan

Before I begin this piece, let me say two things. First, the GCF is to be vigorously commended for its transparency in allowing the Board’s proceedings to be shown, and shown live. And second, it is clear that all the members of the Board are persons of the best possible will.

That said, though, I must confess to having been quite troubled by the several hours of proceedings that I watched, given that these proceedings involved the highest-level decision-making processes of probably the most important single source of public finance for the Paris agreement.

And then there were 8

To briefly sum up what occurred, a profound disagreement emerged over three of the funding proposals before the 16th meeting of the Board. In two of the cases, the issue at stake was the role of the GCF in supporting development banks (and a row over whether it should support hydro power at all). In the third, it was the perceived shortcomings of a major drought adaptation programme in Ethiopia. This eventually became the only project of the nine submitted that was not approved by the Board.

The argument over these proposals basically found developed country Board members on one side and developing country members and civil society observers on the other. The debate cast light not just on this divide, but also on some gaps in the policies and procedures of the Board which – given that this was after all its 16th and not its 1st or 6th meeting – were disturbingly cavernous.

A structure like no other

The GCF appears to be set up like no other fund I have ever come across. Given that it is a mechanism of the UNFCCC and the product – as one Board member pointed out – of a negotiation among climate experts rather than a strategy or vision of financiers, a politicised structure may have been an inevitability early in its life. But 7 years on from its formation, this structure is surely now due for some radical reform.

Like other UN mechanisms, the GCF has a large Board (of 24) representing both donor (essentially developed countries) and recipient (developing country) interests, with private sector and civil society observers. The Board is serviced by a Secretariat, itself supported by a number of ‘Independent Units’ and an Independent Technical Advisory Panel (ITAP) that provides sector and project expertise on funding applications. The Board is the only decision-making body of the GCF and thus has to approve all funding proposals, large or small.

Projects with clear deficiencies come forward, and in almost all cases are approved, but with lengthy conditions attached

The lack of devolution of any powers to the Secretariat is most notable in the project approval process, where it appears that any funding proposal that is properly lodged – i.e. ticks all the boxes required under the process – must be brought to the Board, whether or not it has merit in the eyes of the Secretariat. The result of this is that projects with clear deficiencies come forward, and in almost all cases are approved, but with lengthy conditions attached by the Board in an effort to correct or mitigate the perceived deficiencies.

At the Board meeting I watched, a list of conditions over 12 pages long was drawn up to be attached to the 9 projects before it. (I don’t know what these conditions were, since despite mention of publication they don’t seem to be on the website, and direct requests for the document have not yielded results.)

The setting of conditions in this way is universally agreed to be bad investment practice – like allowing a car to be sold without any foot brakes but by agreement with the driver that he won’t go above 5 KPH and will always keep the handbrake well maintained for stopping purposes. We saw in our piece on the UK’s Green Investment Bank that conditions (or covenants) can be a useful tool, but they should be there to promote good behaviour or prevent bad behaviour, not to compensate for basic flaws in project design.

A tried and tested structure …

So what would a ‘normal’ fund look like and how would it operate?

It’s worth saying in advance that funds with the structure I am about to describe are successfully handling transactions worth multiple times the amounts being handled by the GCF, even if it were to reach $100 billion p.a. of promised flows in the future. So there is no size-related reason why the GCF needs to be structured the way it is.

Also in preface, I am aware it will be argued that the GCF is handling public money and thus needs to have a public procurement approach. That may be true, but if the Fund is also looking to crowd in significant funding from the private sector, then it also needs to operate in ways that don’t put off such engagement. Right now, I think it is telling that only 4 of the 48 accredited entities of the GCF are private institutions.

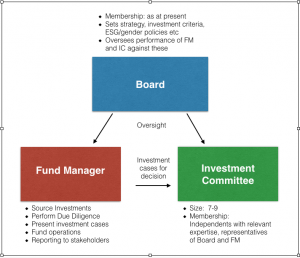

In a regular fund structure (employed by DFIs as well as private institutions, see diagram below), there would be two main operational elements, the fund manager (FM) and the investment committee (IC)[2]. In some funds, where there is a strong ‘mission’ aspect (for example impact investing funds), there may also be an investor advisory group of some kind that acts as mission ‘guardian’.

In such structures, investors will have agreed the fund’s strategies and investment and other criteria (for example ESG* standards) at its inception. The role of the fund manager is to then source investment opportunities, perform ‘due diligence’* and eventually bring forward investment proposals that are in line with the investment criteria to the investment committee, which will make the final decision on them. This committee, typically with a membership in single figures, will have representatives of the fund manager alongside independent members, who represent the interests of investors and will usually outnumber the FM personnel for voting purposes.

Proposals with fundamental flaws should have been either thrown out or corrected in the due diligence phase

Typically, members of the IC will have very strong expertise and relationships in the sector(s) in which the fund invests. Again typically, proposals with fundamental flaws should have been either thrown out or corrected in the due diligence phase, so that IC discussion of proposals is about fine tuning and not about trying to create a whole new instrument (via conditions).

The performance of the FM and IC against the fund’s agreed strategies and criteria will be reported to investors periodically, and may be adjusted by them from time to time via the fund’s constitutional arrangements. Where there is an advisory group of shareholders, this can provide more regular and detailed oversight of the FM and IC’s work and decisions. Such an arrangement is valuable where a fund is investing in new or complex fields, and where the IC’s interpretation of criteria may therefore benefit from an additional source of advice and governance.

…Translated to the GCF

In a setup of this nature, the GCF’s Secretariat would be the ‘fund manager’, while investment decisions would be made by a small investment committee with Secretariat and independent membership, and a couple of donor representatives to create a link to the GCF Board. The role of the Board would then be to monitor the performance of the FM and IC against the agreed criteria, and make adjustments where needed, but it would mainly focus on the kind of ‘big picture’ items which are the proper concerns of Boards, such as overall strategy, risk appetite, ESG and gender policies and high-level relationship building. There might also be transaction limits and very large deals which exceed these limits might also require Board approval (as is common practice elsewhere).

In our view a structure of this kind would allow for the need for a political element to the GCF, but focus the experience and skills of the Board members on matters where they can add real value, while leaving decisions on actual investments to those with the appropriate expertise in that realm. There is no reason either why such a structure should not have strong procurement protections.

In terms of the Fund Manager role, the GCF is already halfway there with the combination of the Secretariat and the Independent Technical Advisory Panel. It just needs to be bolder in giving this fund management team some real devolved power, in tandem with a stable and experienced investment committee.

Unnecessary baggage

At the same time as making structural change, on the evidence of my day’s viewing and reading the materials accompanying the Board’s discussions, there is also a lot of procedural baggage that the GCF is weighing itself (and others) down with, and which could be jettisoned without threatening standards – and indeed might improve them. These include the accreditation process and the paperwork, and the notion of ‘Paradigm Shift’.

On ‘paradigm shift’ there are two issues: Why the insistence on it? And the definition of the concept itself.

The primary purpose of the GCF is surely to crowd in funding as efficiently as possible to the people who need it most. If there are conventional ways to do this successfully, then it is not clear why these should be sacrificed on some altar of compulsory innovation – as was the Ethiopia project.

As to the definition, as deployed at the Board meeting, it seemed questionable. For example, neither acting as ‘junior equity’ to the European Investment Bank or as a grant provider to the EBRD for capacity building seem particularly groundbreaking roles for the GCF. In both these cases, indeed, rather than creating ‘paradigm shift’, the GCF seems to be being used by DFIs as a kind of handy gap-filler in their own mandates. What really needs to happen – and more and more observers are beginning to suggest this [link to ODI/IIED/WRI story] – is that the mandates of the DFIs are themselves changed so that they take on more risk.

If the need for ‘paradigm shift’ is cast in stone in the GCF because it is part of the Governing Instrument (which no one wants to reopen), then the answer is surely for the Board to come up with a list of what is regarded as paradigm shift and what isn’t. (And that, we suggest, would be a far likelier prospect if its job was to focus on such matters and not the detail of project approval.)

Repeating our statement at the outset of this commentary, we believe that the GCF is fuelled by hard work and goodwill. But, for the reasons we highlight in a spirit of constructive critique, we also believe its structure and processes are significantly misaligned with the central role it needs to play in channelling public climate finance responsibly, effectively and efficiently.

While the present ‘muddling through’ approach may be tolerable while the GCF is handling just a few $ billions of transactions a year, if it is seriously setting out its stall as a handler of $20 billion a year (let alone $100 billion) then the present setup is surely unviable.

Time, perhaps, for a Paradigm Shift of its own at the GCF?

[1] Those interested should view Item 14, especially part 5

[2] Or credit committee if loans are being made